My wife periodically recounts to me the first time she ever saw Dolly Parton in person. A young gal from rural Mississippi, she stood in front of Shoney’s on the Parkway in Pigeon Forge for a Dollywood opening day parade. Her 3-year-old daughter twirled at her feet in her new “’Lil Dolly” lacy dress and frilly socks. Spotting Dolly’s float in the distance, she held the little girl up on her shoulders and was suddenly grateful for all that flouncy lace covering most of her face as tears unpredictably rolled down her cheeks until Dolly passed out of sight, releasing some emotion she could not really comprehend, let alone express.

Ever the tormenting husband, I frequently refer back to her tear-filled experience in a quasi-teasing, quasi-adoring fashion, both loving her soft heart and completely failing to understand how someone can come to tears over simply seeing another human being – albeit one of the more spectacular human beings in existence.

I am not entirely exempt myself from swooning a bit at times over people of notoriety, but tears?

Then just last week, the Ladies of Vision of Carson Newman University brought in Ricky Skaggs for a fundraising concert at Knoxville’s new venue, The Mill and Mine.

Just getting tickets brought back great memories of coming to know Ricky Skaggs’ music through sheer unwilling immersion. It was during what I refer to as my period of indentured servanthood to my father, imprisoned in the back seat of his Cadillac and forced to listen music which horrified that era’s self-respecting 11-year-olds such as myself: Charlie Daniels, The Statler Brothers, and of course, Ricky Skaggs.

Pop believed that as long as a man had one of the three playing on the radio, there wasn’t much else a man needed. And somehow, despite my best efforts to resist, Pop’s programming won out and I grew to love the trifecta myself and today keep them readily available on a priority playlist.

In 1982, Highways and Heartaches became Ricky’s first album to go platinum in the United States, and the album contained Pop’s (and eventually my) personal favorite, Highway 40 Blues. For the remainder of the ‘80s, my siblings and I came to believe that a mechanical glitch actually prevented the car from moving forward without a Ricky Skaggs cassette in the radio.

Little did I know it at the time, but those would become some of the most precious memories in my life, and listening to Highway 40 Blues while I drive down the road even today, I can feel Pop beside me, straining to harmonize and tapping out the rhythm as our hearts join in pouring out the joy evoked by the plucking of mandolin strings by this man from Kentucky.

Fans of Ricky Skaggs know that he has “returned to his roots” and plays bluegrass almost exclusively again, so I went in not expecting to revisit his country music hits. Given my love for bluegrass, I was perfectly content and hoped I might get to hear Uncle Penn live and in person.

As the evening drew to a close, Ricky announced his last song. “Let it be Uncle Penn,” I silently begged. He mentioned it was one of his greatest hits. “Yes! Uncle Penn!” I hoped with growing excitement.

Then Ricky remarked that he thought about this song every time he drove through Knoxville, and I immediately knew that he was about to sing Highway 40 Blues. I slid back in my chair, absorbing this reality. I was sitting two tables back from Ricky Skaggs on-stage about to play the song that I had sung with my father more than any other in our short 20 years together. It was the traditional start and finish to all the many summer road trips I took with him on his journeys as a traveling salesman.

But I was not prepared emotionally for this turn of events and momentarily considered fleeing to the back of the room where I could break down in privacy. Instead, while the words I knew so well echoed from the stage, I waged a bittersweet struggle to maintain my composure, tapping my foot yet unable to open my mouth and sing along without wholly losing the battle, and the song in all its splendor came and went.

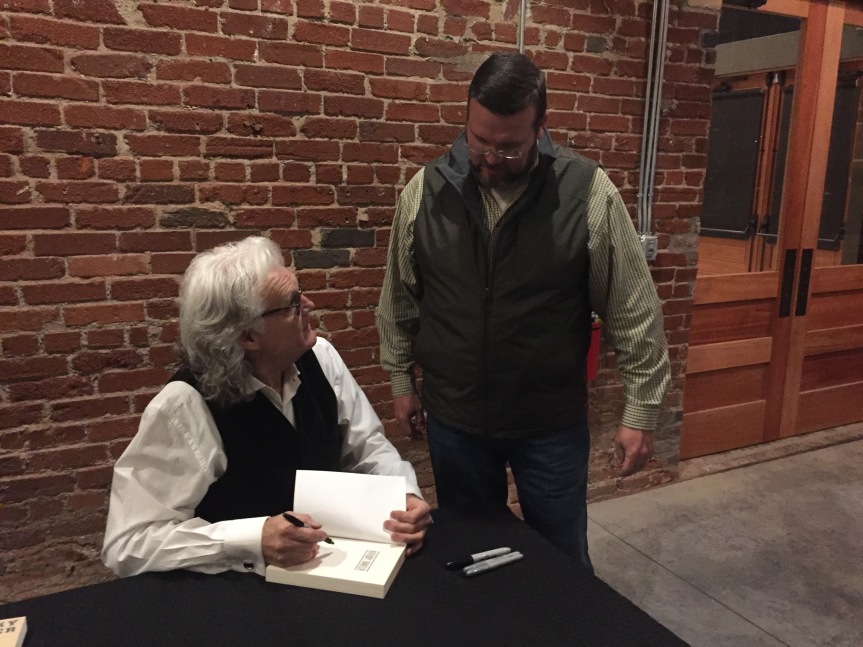

As Ricky thanked the audience for supporting a great cause, I recovered sufficiently from my emotion to join the line for an autographed copy of his new book, Kentucky Traveler, recounting his life in music from the day his father put a mandolin in his hand at age five.

Waiting in line, I rehearsed what I would say over and over, and eventually my turn came. I uttered something about how much my father adored him and how I wished he could have seen Ricky perform live before he passed away in 1990. For a moment, Ricky paused and looked directly at me and told me about his father passing in 1996 and how not a day had passed since then that he hadn’t thought about his father and missed him dearly but he held onto the knowledge that he would see him again one day.

As tears swelled again in the corners of my eyes, I nodded, again unable to voice the words I wanted to say. “I know, Ricky, I know.”

© Michael L. Collins

* This column previously appeared in the November 16, 2016 edition of The Mountain Press

If you enjoyed this column and would like to see more, click here.